|

Introduction

Hey there, folks. If you’re reading this, chances are you’re facing some tough times with someone you love. Maybe it’s your child, your sibling, or your partner, and you’re watching them struggle with addiction, trauma, or mental health challenges. Trust me, I’ve been there. For over 20 years, I’ve walked alongside families just like yours, helping them navigate the rocky terrain of these issues. And let me tell you, there’s one thing I’ve learned that’s absolutely crucial: the power of updating the self. Understanding Trauma and Its Impact Let’s start with the basics. Trauma isn’t just about the big, dramatic events like car accidents or natural disasters. It can also stem from more subtle, insidious experiences like neglect, emotional abuse, or even the constant stress of living in a chaotic environment. Whatever its form, trauma has a way of worming its tendrils deep into our psyche, shaping the way we see ourselves and the world around us. I remember working with a family whose teenage son had been through some pretty rough stuff. His experience of addiction was just the tip of the iceberg. As we peeled back the layers, we discovered a history of childhood trauma that had been silently shaping his behavior for years. It was like watching a puzzle come together — suddenly, everything made sense. The Role of Self-Reflection and Self-Awareness Now, here’s where things get interesting. Trauma has a sneaky way of distorting our self-perception. It plants seeds of doubt, whispers of unworthiness, and before we know it, we’re trapped in a web of negative beliefs about ourselves. But here’s the good news: we have the power to break free. One of the most powerful tools in our arsenal? Self-reflection. Taking the time to really look inward, to question our beliefs and assumptions, can be incredibly liberating. I remember working with a mom who was struggling to understand her daughter’s erratic behavior. Through our conversations, she began to see how her own past experiences were coloring her perceptions — and how she could rewrite her story in a way that empowered both herself and her daughter. Navigating the Journey of Self-Update So, how do we go about updating our self-model? It’s not always easy, I’ll admit. It takes courage, patience, and a whole lot of self-compassion. But trust me when I say it’s worth it. One strategy I often recommend is journaling. There’s something incredibly cathartic about putting pen to paper and letting your thoughts flow freely. Another approach is mindfulness — simply taking a few minutes each day to pause, breathe, and check in with yourself can work wonders. And don’t be afraid to seek support. Whether it’s through therapy, coaching, support groups, or just talking things out with a trusted friend, having someone by your side can make all the difference. Addressing Barriers and Challenges Of course, updating your self-model isn’t always smooth sailing. There will be obstacles along the way — doubts, fears, old habits die hard. But here’s the thing: every stumble is an opportunity to learn and grow. I remember working with a dad who was struggling to let go of his need for control. He was so used to trying to fix everything for his son that he couldn’t see how his actions were actually hindering his son’s recovery. But through gentle encouragement and a whole lot of patience, he learned to loosen his grip and trust in his son’s ability to find his own way. Integrating Self-Update into Daily Practice As we wrap up, I want to leave you with one final thought: updating your self-model isn’t a one-time thing. It’s an ongoing journey, a lifelong commitment to growth and self-discovery. So don’t be afraid to keep exploring, keep questioning, keep updating. Your future self will thank you for it. And remember, you’re not alone in this. Reach out to your fellow travelers, lean on your support network, and above all, be kind to yourself. You’re doing the best you can, and that’s more than enough. Conclusion So there you have it, folks. The path to healing isn’t always easy, but it is possible — and updating your self-model is a crucial step along the way. So take a deep breath, trust in the process, and know that brighter days are ahead. You’ve got this. And if you ever need a helping hand along the way, I’ll be right here cheering you on. Until then, take care and keep updating. Author Bio: As a family coach with over 20 years of experience, I’ve had the privilege of walking alongside families as they navigate the ups and downs of addiction, trauma, and mental health challenges. My passion is helping others discover their inner strength and resilience, and I’m honored to be a part of their journey toward healing and wholeness. If you’d like to learn more about my work or connect with me personally, feel free to reach out --I’d love to hear from you.

0 Comments

Addiction is a complex, multifaceted issue that doesn’t just affect the individual — it impacts the whole family. Drawing from two decades of experience in family coaching, I’ve observed the transformative power of a supportive, understanding family environment in the journey towards recovery. This article explores how families can use principles from the Swiss model of addiction treatment to create a nurturing space for young adults grappling with addiction and emotional health challenges.

The Swiss model for addiction treatment, renowned for its progressive and humane approach, offers a compelling framework for addressing the complexities of drug addiction. At its core, this model integrates a comprehensive range of services that prioritize harm reduction, easy access to medical care, and a non-punitive, health-centered approach. Unique in its utilization of medication-assisted treatments, including the regulated prescription of substances like heroin for severe cases, Switzerland has successfully reduced the stigma around addiction, leading to better public health outcomes and a significant decrease in drug-related deaths. For families, the Swiss model provides a blueprint for supportive, compassionate involvement in the recovery process. It emphasizes the importance of treating addiction as a medical issue rather than a moral failing, which can help reduce shame and foster a supportive environment at home. This approach encourages open dialogue, strengthens familial bonds, and promotes healing by addressing the underlying emotional and psychological factors contributing to addiction. In exploring how Swiss principles can be applied in different contexts, families gain valuable insights into nurturing recovery and resilience in their loved ones. Understanding Addiction as a Family System Issue Addiction often signals unmet needs within the individual’s emotional or psychological landscape, which can be reflective of broader family dynamics. It’s crucial for families to not approach the experience of addiction as a personal failing of the individual, but as a symptom of something larger affecting the whole family system. Embracing Compassionate Inquiry A method I talk about is the practice of compassionate inquiry. This approach involves deep, empathetic listening without trying to fix or judge. By asking open-ended questions about your loved one’s experiences and feelings, you create a space for them to express themselves without fear of repercussion. For example, rather than saying, “Why can’t you stop using?”, try asking, “What are you feeling when you feel the urge to use?” This shift in dialogue can reveal underlying issues that contribute to addictive behaviors, such as stress, trauma, or a need for belonging. The Role of Connection and Belonging Addiction thrives in isolation, but it diminishes in a supportive community. Johann Hari famously said that the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, but connection. Families play a crucial role in reinforcing this connection. Fostering a Sense of Belonging Creating a home environment where everyone feels accepted and understood is essential. Regular family activities, even simple ones like shared meals or game nights, can strengthen the bonds and improve communication. One family I coached established a weekly ‘family circle’, where each member shared their feelings and struggles without interruption or judgment, significantly improving their dynamics and support for their recovering member. Integrating Body and Mind in Recovery The connection between trauma and addiction is significant. Trauma can reside in the body, and somatic experiencing can help release this trauma, thereby aiding in addiction recovery. Incorporating Body-Awareness Practices Integrating practices such as yoga, mindfulness, or even simple breathing exercises can help manage anxiety and stress, common triggers for resumption of use. Encouraging your loved one to engage in these activities, and participating with them, can not only improve their coping mechanisms but also enhance your emotional connection. Collaborative and Non-confrontational Approaches Adopting a collaborative approach to recovery can change the traditional dynamic of caregivers and care receivers, fostering an environment where the young adult feels supported and part of the decision-making process. Encouraging Positive Behavioral Support Incentives can be more effective than punishments in motivating change. For example, setting clear, achievable goals together with appropriate rewards can encourage progress and commitment. Additionally, establishing boundaries with love and respect is critical. It’s not about setting rules that punish, but about agreeing on boundaries that safeguard everyone’s well-being. Embracing Vulnerability and Authenticity Vulnerability is a cornerstone of trust and connection. When families can share their vulnerabilities, it fosters a deeper understanding and empathy. Modeling Vulnerability as a Strength By sharing your own fears and failures openly, you show that vulnerability is not a weakness but a strength. This modeling can encourage your loved one to express their vulnerabilities and struggles, which is a critical step in the healing process. Conscious Parenting in the Context of Addiction The principles of conscious parenting can be incredibly effective in navigating the challenges of addiction. This approach emphasizes awareness, acceptance, and the absence of ego in the parenting process. Aligning Expectations with Realities It’s important to manage expectations, both yours and your loved one’s. Recognizing that recovery is a non-linear process helps in maintaining patience and support through setbacks. An attitude of acceptance, rather than one fixated on change, can significantly relieve pressure on the young adult, allowing them to progress in their own time and way. Conclusion The journey towards recovery is a path of growth for both the individual and their family. By adopting a holistic approach inspired by the Swiss model, and integrating methods that foster healing and connection, families can create a supportive environment where young adults can flourish in recovery. Remember, you’re not just navigating addiction; you’re nurturing a future where your loved one can thrive. Further Resources For families looking to deepen their understanding and find additional support, consider exploring books, workshops, and community groups focused on addiction recovery and family dynamics. Engaging with professional family coaching will provide tailored guidance and support. Recovery is not just about stopping the use of substances; it’s about starting a journey towards a connected, fulfilling life. Let’s take that step together. Introduction

As a family coach with two decades of experience, I've seen firsthand the struggle and resilience of families navigating the turbulent waters of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) and mental/emotional injuries. These challenges are pervasive, affecting countless young people across all walks of life. Often, the behaviors we see in these young individuals—behaviors that may appear illogical or self-destructive—are actually survival strategies. To truly support our children, we need to shift our perspective and approach with empathy and understanding. The Link Between Trauma and Substance Use as Survival Strategies Understanding the Brain's Survival Mechanism In my years of coaching, I've observed that many children and adolescents use substances as a way to cope with the overwhelming emotions and pain that stem from traumatic experiences. This isn't just about poor choices or a lack of willpower; it's about survival. When the brain is traumatized, it doesn't prioritize long-term outcomes or logical thinking. Instead, it focuses on immediate relief from pain, which can make substances appealing as they provide a temporary escape. Personal Anecdote: A Shift in Perspective I remember working with a young man, let’s call him Alex, whose substance use began shortly after he lost a parent. Initially, his behavior was viewed through a lens of delinquency, but when we shifted to see his drug use as a coping mechanism for his immense grief and loss, the approach to his treatment transformed. This shift not only changed how his family interacted with him but also how he viewed his own actions and potential for recovery. The Power of Empathy in Treatment Building a Foundation of Compassion Empathy is more than just understanding someone's feelings—it's about connecting with their emotional state and showing that their experiences are valid. This connection is crucial for children suffering from addiction and trauma. A non-judgmental approach fosters an environment where they can open up about their struggles without fear of reprisal or misunderstanding. Why Empathy Matters In practice, empathy might look like listening more than talking, validating the child’s feelings, and asking what they need instead of assuming. Such approaches can make all the difference. Empathy leads to better engagement in treatment and helps reduce the stigma that often surrounds addiction and mental health challenges. Implementing Trauma-Informed Care Key Principles of Trauma-Informed Care Trauma-informed care is based on the understanding of the prevalence and impact of trauma. It involves recognizing symptoms of trauma in all aspects of behavior and responding by integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices. The aim is not to treat every child the same but to tailor the approach to individual needs, ensuring that the care provided does not inadvertently re-traumatize. Applying Trauma-Informed Practices For parents, implementing trauma-informed care can mean educating themselves about trauma, understanding how it can manifest in behaviors, and adjusting their responses accordingly. It also means advocating for schools and healthcare providers to adopt trauma-informed approaches. The Necessity of Holistic and Integrated Treatment Approaches Treating the Whole Person Addiction and trauma are not isolated issues—they are deeply interconnected with psychological, social, and biological factors. Effective treatment must address all these dimensions. This might include therapy for trauma, support groups for addiction, and medical care for any physical health issues. Integration in Action Consider the approach of using therapies that focus not just on talking but on physical movement and somatic experiencing. These methods help children reconnect with their bodies, a crucial step in healing trauma. In my practice, incorporating mindfulness exercises has also proven effective in helping young people manage stress and reduce reliance on substances. Building Resilience and Promoting Autonomy Encouraging Healthier Coping Mechanisms Resilience can be fostered by helping children identify their strengths and develop healthier coping strategies. This involves coaching them to recognize their feelings, understand their triggers, and choose responses that align with their long-term goals. Supporting Self-Efficacy and Choice Promoting autonomy involves empowering children to take an active role in their recovery. This means involving them in discussions about treatment options and respecting their choices. When children feel they have a say in their treatment, they are more likely to engage actively and persistently. Fostering Community and Connection The Role of Supportive Communities Recovery thrives in a supportive community. This includes not only family and friends but also peers who are going through similar experiences. Support groups and community resources can provide essential emotional scaffolding. Building a Network Creating and maintaining a supportive network involves regular family meetings, participation in community events, and connecting with other families dealing with similar issues. This network not only supports the child but also helps the entire family navigate the recovery process. Conclusion By recognizing that behaviors associated with addiction and trauma often stem from a place of survival rather than a failure of logic, we can begin to see our children in a new light. This understanding opens the door to treatments that are more compassionate, effective, and supportive. I encourage all parents to seek out and advocate for care options that embrace this holistic, empathetic approach to healing. Call to Action: Embrace the Journey Together As we conclude, I urge you, the parents and guardians of young individuals facing addiction and emotional trauma, to embrace the journey of recovery with empathy, understanding, and commitment. Remember, you are not alone in this challenge, and the path to healing is a collective endeavor that requires patience, compassion, and persistence. Take proactive steps today by engaging with communities that share your experiences, and advocate for the adoption of trauma-informed care in all aspects of your child’s life. Learn more about the integrated approaches to treatment that consider the whole person, not just the symptoms. Encourage and support your child in building resilience, embracing healthier coping mechanisms, and fostering a sense of autonomy in their recovery process. Moreover, consider reaching out for professional guidance tailored to your family's specific needs. Whether through counseling, family coaching, or therapeutic services, the right support can make a significant difference in navigating the complexities of addiction and trauma recovery. Let’s move forward together, creating an environment where our children can heal, grow, and thrive. Your active participation and advocacy can transform not just your child’s life but also contribute to a broader cultural shift towards more compassionate and effective approaches to dealing with substance use and mental health challenges. Remember, every step you take is a step towards recovery and resilience for your child. Let's take these steps together. In my two decades of journeying with families through the thickets of addiction, mental, and emotional health challenges, a profound truth has repeatedly emerged: the path to healing is both personal and collective. As we navigate these tumultuous waters, a perspective shift is vital. It’s time to view overdose not as a series of isolated incidents of personal choice but as the outcomes of broader policy decisions. This realization doesn’t absolve individuals of responsibility but rather illuminates the power of context, policy, and societal influence in shaping the terrain of addiction.

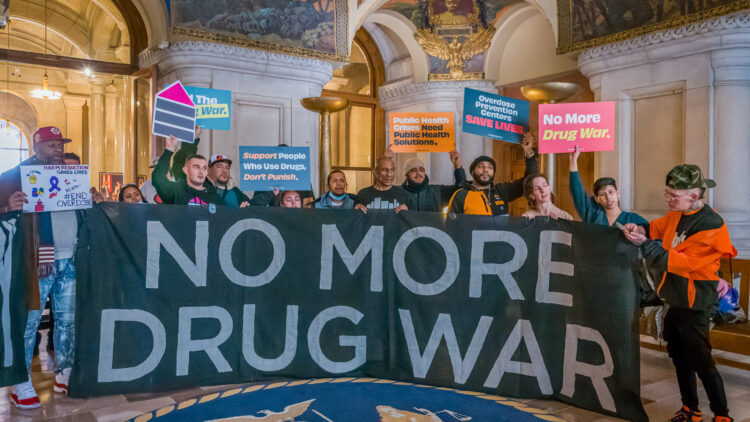

Understanding Addiction Beyond Choice The Nature of Addiction Addiction, as I’ve learned from countless families, is far more than a series of poor decisions. It’s a complex dance of genetics, environment, trauma, and unmet emotional needs. Addiction often roots in a deep-seated pain, a manifestation of an unhealed wound. It’s a misguided quest for solace, a distorted form of self-medication against the unbearable weight of past hurts, current stresses, and future anxieties. Societal Stigma and Misunderstanding Our societal approach to addiction and overdose has been marred by stigma and oversimplification. We’ve been led to believe that addiction is solely a personal failure, a lack of willpower. This belief system not only alienates those struggling but also blinds us to the structural inadequacies that foster addiction. It’s essential to challenge these myths, fostering a community of understanding and support. The Impact of Policy on Drug Use and Overdose Policies — ranging from drug prohibition and criminalization to the lack of accessible, comprehensive treatment options — play a significant role in the overdose crisis. By prioritizing punitive measures over harm reduction and treatment, we inadvertently increase the harm associated with drug use, including the risk of overdose. The Case for Harm Reduction and Decriminalization Harm reduction strategies acknowledge the reality of drug use and seek to minimize its negative consequences without necessarily requiring cessation of use as a precondition for support. Decriminalization, on the other hand, can reduce the stigma around drug use, making it easier for individuals to seek help. These policy choices can significantly decrease the incidence of overdose and support more compassionate, effective approaches to addiction. The Family’s Journey Through the Maze of Addiction Navigating a loved one’s addiction is a journey fraught with confusion, pain, and often, a sense of helplessness. It requires a balance of empathy, boundaries, and self-care that many find challenging to maintain. The Emotional Rollercoaster The families I’ve worked with describe the experience as an emotional rollercoaster. One day, there’s hope; the next, despair. In these moments, understanding the nature of addiction is crucial. Recognizing it as a disease rather than a moral failing can help families approach their loved ones with empathy and compassion, laying the groundwork for effective support. Navigating Systemic Barriers to Help The systemic barriers families encounter when seeking help for their loved ones can be overwhelming. From insurance hurdles to the scarcity of treatment options that address the individual’s specific needs, the journey can be daunting. Advocacy becomes a critical tool in navigating these challenges, pushing for a system that supports rather than punishes. Advocating for Change: The Role of Families Families are not powerless in the face of addiction. By coming together, sharing stories, and advocating for policy change, they can be a formidable force in shifting the narrative and approach to overdose and addiction. From Personal to Policy Advocacy Personal advocacy — supporting a loved one through their recovery journey — is critical. But policy advocacy is where substantial systemic change occurs. Families can join or form advocacy groups, participate in policy discussions, and support harm reduction initiatives, contributing to a broader shift towards more humane, effective approaches to addiction. The Power of Community In advocating for change, there’s strength in numbers. Connecting with other families facing similar challenges can provide not only emotional support but also a collective voice that’s harder to ignore. Together, families can push for policies that prioritize health and support over punishment and stigma. Creating a Supportive Environment for Recovery Embracing a Trauma-Informed Approach Understanding that much of addiction stems from trauma is pivotal. A trauma-informed approach recognizes the prevalence of trauma and its profound impact on the individual’s life and recovery journey. This approach involves creating a safe, supportive, and non-judgmental environment where healing can begin. It’s about acknowledging the person’s worth beyond their addiction, understanding their behavior in the context of their experiences, and providing support that addresses the root causes of their distress. Strategies for Family Support Families can play a crucial role in creating this environment. This involves:

Moving Forward with Compassion and Advocacy Changing the Narrative As a society, we need to shift our narrative around addiction and overdose from one of blame to one of understanding and support. Every story shared, every voice raised against the current punitive system, adds to a chorus calling for change. By openly discussing addiction and challenging the stigma, we contribute to a more compassionate society. The Role of Policy in Prevention and Treatment Effective overdose prevention and addiction treatment are not just about individual recovery; they are about shaping policies that support health and well-being for all. This includes advocating for:

A Collective Call to Action We stand at a crossroads. The path we choose can lead us towards healing and understanding or back down the road of punishment and stigma. As families, as communities, we have the power to influence this decision. By advocating for compassionate, evidence-based policies, by supporting one another in our journeys, and by treating every individual with dignity and respect, we can make a difference. Conclusion: A New Path Forward The overdose crisis is a complex issue that requires a nuanced, compassionate response. As a family coaching expert, I’ve seen the power of empathy, understanding, and informed support in navigating the challenges of addiction and mental health. It’s clear that overdose is not merely a personal choice but a reflection of broader policy choices. By recognizing this, we open the door to more effective, humane approaches to prevention and treatment. The journey ahead is not easy, but it is hopeful. Together, we can forge a new path forward — a path marked by compassion, understanding, and a commitment to change. Let this be our collective mission: to create a world where overdose is no longer seen as a moral failing but as a call to action for us all. Introduction

In my two decades of working closely with families navigating the tumultuous seas of addiction and mental health challenges, I’ve witnessed the profound impact that understanding and empathy can have on healing. The journey of supporting a young adult through these challenges is a delicate balance of love, boundaries, and informed decision-making. The recent advancements in genetic testing for predicting the risk of opioid dependence, as highlighted by the work of Yale scientists, offer a new frontier for families. However, it comes with its own set of complexities and ethical considerations. This article aims to provide clarity and guidance for families considering genetic testing as part of their strategy to address addiction and mental health issues. Understanding the Landscape of Genetic Testing The Promise of Prediction Genetic testing holds the promise of offering insights into the likelihood of developing opioid dependence, among other conditions. This could theoretically allow families and healthcare providers to tailor prevention and treatment strategies more effectively. But the reality is nuanced. Genetic factors, while informative, are just one piece of the puzzle. The Biopsychosocial Model: A Holistic View The biopsychosocial model underlines addiction as a condition influenced by a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. This model suggests that addressing addiction requires a holistic approach, considering not just genetic predispositions but also emotional well-being, environmental factors, and social support systems. The Role of Trauma and Environmental Factors Beyond Genetics: The Impact of Trauma In my years of coaching, I’ve seen time and again how trauma and adverse life experiences play a critical role in the development of addiction and mental health challenges. The recent research underscores this, showing that factors such as a history of PTSD can significantly increase the risk of opioid dependence, independent of genetic factors. The Importance of Context Families get to understand that while genetic testing can provide some insights, it cannot capture the full context of an individual’s life experiences, emotional state, and the external environment. These aspects are often more telling of a person’s vulnerability to addiction than genetic markers alone. Navigating the Decision to Pursue Genetic Testing Considering the Pros and Cons Before deciding on genetic testing, it’s crucial to weigh the benefits against the potential drawbacks. While the knowledge gained from testing can be empowering, it can also lead to ethical dilemmas, privacy concerns, and the risk of stigma. Families should consider these factors carefully, ideally with the guidance of a healthcare professional who understands the complexities of addiction. The Potential for Misinterpretation One of the challenges with genetic testing is the risk of misinterpretation. A genetic predisposition does not guarantee the development of an addiction, nor does the absence of certain genetic markers eliminate the risk. Families must approach the results with an understanding of their limitations and a commitment to using the information as one part of a broader strategy. A Compassionate Approach to Support Building a Supportive Environment Regardless of the decision to pursue genetic testing, creating a supportive and nurturing environment is paramount. This includes open communication, setting healthy boundaries, and fostering a non-judgmental space where young adults feel safe to share their struggles and achievements. The Power of Connection Connection is at the heart of healing. By fostering strong, empathetic relationships within the family, parents can help mitigate the feelings of isolation and shame that often accompany addiction and mental health challenges. Remember, it’s about connecting with the person behind the behavior, understanding their needs, and supporting them in finding their path to healing. Practical Steps for Families Educate Yourself and Your Family Knowledge is a powerful tool. Educate yourself and your family about addiction, the biopsychosocial model, and the potential implications of genetic testing. Understanding the complexity of these issues can foster empathy and resilience within the family. Seek Professional Guidance Navigating the waters of genetic testing and addiction treatment can be overwhelming. Don’t hesitate to seek the support of professionals who specialize in addiction, mental health, and genetic counseling. They can provide valuable insights and guidance tailored to your family’s unique situation. Foster Open Communication Encourage open and honest communication within your family. Discuss your fears, hopes, and the potential outcomes of genetic testing without judgment. Remember, the goal is to support each other through understanding and empathy. Embrace a Holistic Approach to Healing Consider incorporating holistic practices into your family’s approach to healing, such as mindfulness, therapy, and community support groups. These practices can complement traditional treatment methods and support the overall well-being of your loved one. Closing Thoughts In my journey alongside families facing the challenges of addiction and mental health, I’ve learned that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. Each family’s journey is unique, filled with its own challenges and triumphs. Genetic testing for opioid dependence risk represents a new tool in our collective toolkit, but it’s important to remember that it’s just that — a tool. The heart of healing and support lies not in a test result, but in the connections we forge, the understanding we cultivate, and the compassionate support we offer to our loved ones struggling with addiction and mental health challenges. As families consider the path of genetic testing, I urge you to view it within the broader context of your loved one’s life. Remember, the roots of addiction often lie deep within a complex tangle of emotional pain, trauma, and unmet needs. Genetic predispositions may provide some insights, but they do not define destiny. The journey towards healing is multifaceted, requiring patience, compassion, and a holistic approach that addresses not just the symptoms, but the underlying causes. Professional Anecdotes for Insight In my practice, I’ve encountered families who discovered a sense of empowerment through genetic testing — it gave them a new perspective on their loved one’s challenges and informed their approach to support. However, it’s crucial to pair this scientific insight with a deep, empathetic understanding of the person’s lived experience. One family, in particular, found that their engagement with their child’s recovery process deepened after recognizing the genetic components of their struggle. Yet, they also realized that their unwavering emotional support and commitment to understanding were equally vital in their child’s journey towards healing. Conversely, I’ve witnessed families who, upon receiving genetic testing results, felt a sense of determinism that overshadowed the individual’s capacity for growth and change. It’s a poignant reminder that while genetics can influence predispositions, they do not cement fate. The resilience of the human spirit, supported by love, understanding, and appropriate interventions, can overcome many predisposed challenges. Moving Forward with Hope and Understanding For families standing at the crossroads of deciding whether to pursue genetic testing, remember: that your love, understanding, and support are the most potent medicines. Engage in open dialogues, seek professional guidance, and remember that the path to healing is a journey of collective growth, learning, and unconditional love. Embrace the tools available, but anchor your journey in the profound connections that bind you as a family. Let the knowledge you gain, whether through genetic testing or through deepening your understanding of addiction and mental health, be a guide — not a verdict. Together, with compassion as your compass, you can navigate the challenges and celebrate the victories on the path to wellness. As you move forward, let the stories of those who’ve walked this path before you inspire and guide you. Remember, you are not alone in this journey. A community of professionals, support groups, and countless families share your hopes and your fears. Lean on this community, share your experiences, and draw strength from the collective wisdom and support available to you. Conclusion The journey of supporting a loved one through addiction and mental health challenges is one of the most profound expressions of love and commitment. It’s a journey that tests and reveals the strength of family bonds. As you consider the role of genetic testing in this journey, let it be with clarity, compassion, and a deep commitment to supporting your loved one in a way that honors their full complexity, their capacity for change, and their inherent worth as individuals. Your love, understanding, and support are the foundation upon which any path to healing is built. You Won’t Believe How This New Drug Could Revolutionize Addiction Treatment — But Is It Enough?3/22/2024 The Buzz Around GLP-1 Medications

The excitement surrounding the early data on GLP-1 medications like Ozempic and Wegovy for addiction treatment is indeed a sign of progress in our understanding of complex health issues. However, it’s essential to consider the broader picture of addiction beyond the biochemical aspects. The focus on pharmaceutical interventions alone may overlook the critical dimensions of emotional, psychological, and social factors that contribute to addiction. The disease model of addiction, while useful in some respects, might not fully encompass the complex interplay of individual experiences, trauma, and societal influences that shape addictive behaviors. Critiquing the Pharmaceutical Approach and the Disease Model of Addiction Drawing upon a more holistic understanding of health and well-being, it’s crucial to emphasize that true healing often requires addressing the root causes of distress and disconnection that many individuals facing addiction experience. For instance, understanding the role of unresolved trauma, the impact of social isolation, and the lack of meaningful connections can offer deeper insights into the nature of addiction. These perspectives advocate for an integrated approach to treatment, one that combines medical interventions with therapeutic, community-based, and supportive strategies that foster emotional healing and resilience. Advocating for a Holistic View on Recovery Moreover, the critique of the pharmaceutical industry’s role and the health system’s priorities highlights a systemic issue in how we address health crises. The pursuit of new treatments is vital, yet it’s equally important to question whether our current health paradigms adequately serve the well-being of individuals and communities. The emphasis on medication as the primary solution may inadvertently neglect the significance of preventative measures, social support systems, and accessible, holistic care options that can empower individuals to navigate their recovery journeys more effectively. Navigating Toward Integrated and Compassionate Care Solutions In this light, while new medications like GLP-1 drugs offer promising avenues for reducing the physiological cravings associated with addiction, they should not be viewed as standalone solutions. Instead, embracing a more expansive view of health — one that incorporates the emotional, social, and psychological dimensions of addiction — can lead to more compassionate, comprehensive, and effective approaches to healing and recovery. This perspective encourages a shift towards treatments that not only alleviate physical symptoms but also address the underlying pain, fostering a sense of connection, purpose, and empowerment for those navigating the challenges of addiction. Conclusion The exploration of GLP-1 medications like Ozempic and Wegovy offers a glimmer of hope in the realm of addiction treatment, hinting at the possibility of groundbreaking advancements. However, this optimism must not overshadow the critical need for a more nuanced understanding of addiction — a condition that is as much about the human experience as it is about biological mechanisms. By critiquing the prevailing pharmaceutical approach and challenging the narrow confines of the disease model, we open the door to more compassionate, holistic, and effective solutions for those grappling with addiction. Embracing a comprehensive view that includes emotional healing, social support, and psychological resilience alongside medical interventions can pave the way for a future where recovery is not just about managing cravings but about fostering a deeper sense of well-being and connection. The path forward is one of integrated care, where the dignity and complexity of the human spirit are at the heart of addiction treatment. As parents, witnessing your young adult child struggle with mental health challenges, addiction, or trauma can evoke a deep sense of helplessness and concern. Drawing on insights from the realms of mindfulness, psychology, and the transformative power of self-forgiveness, I offer a comprehensive guide to empower you and your entire family in supporting each other through these turbulent times.

Embracing the Complexity of Human Nature Recognize that making mistakes and facing challenges are intrinsic parts of the human experience. Our inner critic often holds us to unrealistic standards, fueling a cycle of self-recrimination and guilt. It’s essential to understand that this critical voice is not a reflection of truth but a barrier to healing and growth. I encourage your family to embrace their humanity, acknowledging mistakes as opportunities for learning and self-discovery. The Power of Self-Forgiveness Self-forgiveness is a cornerstone of emotional healing. It involves acknowledging our past errors and extending compassion to ourselves, allowing us to release the burden of guilt and shame. Share with your family the concept that forgiveness is not about forgetting or excusing harmful actions but about freeing oneself from the chains of past regrets. This act of self-compassion opens the door to healing and fosters a nurturing environment for personal growth. Cultivating a Forgiving Mindset Encourage your family to adopt a practice of self-forgiveness, guiding all of you to reflect on past actions with kindness and understanding rather than judgment. This process helps to mitigate the harshness of the inner critic, enabling a more loving and accepting view of oneself. Through meditation, journaling, or thoughtful conversation, everyone can learn to recognize their worth and potential beyond their mistakes. Nurturing Connection Through Compassion Building strong, compassionate relationships is crucial in supporting your family. Demonstrating unconditional love and acceptance can significantly impact our ability to heal and thrive. Engage in open, empathetic communication, providing a safe space for family to express their vulnerabilities and challenges without fear of judgment. This connection not only strengthens your relationships but also reinforces a sense of belonging and support. Promoting Holistic Well-being All family members get to engage in practices that enhance the mind-body connection, such as mindfulness, yoga, or nature walks. These activities can help alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression, fostering a sense of peace and well-being. Incorporating self-forgiveness and mindfulness into your daily routines can also enhance emotional resilience, enabling a more compassionate and gentle approach to oneself and others. The Role of Professional Support Seeking professional help is a vital step in navigating mental and emotional health challenges. Therapists, counselors, coaches, and support groups offer valuable resources and guidance for your family. Emphasize the importance of professional support as a partnership in the healing journey, respecting each family member’s autonomy and preferences in choosing the right path for them. Conclusion: A Journey of Healing and Growth Supporting your family through their struggles is a journey marked by patience, understanding, and love. Integrating the principles of self-forgiveness and compassion into your approach can transform the healing process, providing a foundation for lasting change. Remember, the path to recovery is paved with small steps of progress, each one a testament to the strength and resilience of the human spirit. Take the Next Step Towards Healing and Empowerment The journey of supporting your family through their challenges is a path filled with both hurdles and milestones. By embracing and then demonstrating the principles of self-forgiveness and understanding, you are laying down a foundation of compassion, resilience, and unconditional support. But the conversation doesn’t have to end here. If this article resonated with you, if it sparked a question, or if you found yourself nodding along, we invite you to take the next step:

🔗 Join Our Community | 🔗 Schedule a Consultation Take the first step towards a brighter, more supportive future today. Introduction

In our fast-paced world, finding moments of tranquility and introspection can sometimes feel like a distant dream. Yet, dedicating time for self-reflection is essential for personal growth, mental health, and emotional resilience. This blog post invites you on a week-long journey starting from today, to explore mindfulness, combat negative thoughts, and foster a deeper connection with yourself. Day 1: Embracing Presence and Combatting Negative Thoughts Our journey begins with mindfulness. Recognize when negative thoughts arise and bring your attention to your breath or your immediate surroundings. This practice of mindfulness will help you understand the triggers of these thoughts and how to gently steer your focus back to the present. Day 2: Mindfulness Meditation and Symptom Management Mindfulness meditation can be a powerful tool in managing intrusive thoughts. By acknowledging these thoughts without judgment and returning your focus to your breath or a chosen mantra, you can begin to alter your response to subconscious cues. Reflect on how this practice modifies your usual reactions to such thoughts. Day 3: Integrating Heart and Mind — Sunday Reflect or journal about times when your heart and mind were in harmony. Identifying activities or practices that facilitate this feeling of integration can enrich your daily life. Day 4: Deserving Grace and Space Contemplate your personal journey and the obstacles you’ve navigated. Challenge the notion that you don’t deserve grace and space to explore and understand yourself. A self-written letter of forgiveness and understanding can be a cathartic step in this process. Day 5: Small Actions, Big Mindset Shifts Initiate your day with a small, purposeful action that aligns with your broader goals or brings you joy. This act of intentionality can significantly influence your mood and outlook for the day. Day 6: Priming for Future Experiences Treat yourself with the kindness and respect you wish to receive from others. Reflect on how self-compassion can prepare you for future experiences by establishing how you deserve to be treated. Day 7: Sharing and Reflecting on Progress Conclude your week by sharing your experiences with someone supportive. Reflect on the changes in your actions and mindset. Consider what adjustments could further your progress and how this week has affected your approach to self-judgment and overthinking. This week of daily reflections is more than a series of tasks; it’s a journey towards self-awareness and self-compassion. As you embark on this path, remember that the goal is not to achieve perfection but to make progress. Allow yourself the grace to explore, adjust, and grow. This exploration can lead to a richer, more fulfilling life, rooted in mindfulness and self-compassion. Understanding and supporting a loved one through addiction and mental health challenges is a journey that requires patience, empathy, and a deep appreciation for the complexity of human emotions and behaviors. It’s not a path marked by simple solutions or quick fixes but rather a nuanced exploration of understanding and healing. This guide aims to arm you, the parents and family members, with perspectives and tools to navigate this difficult terrain, drawing from a well of wisdom that emphasizes compassion, connection, and holistic care.

Understanding the Landscape The Diversity of Experience Every journey through addiction and mental health challenges is unique. While one person may find themselves caught in the grips of substance abuse following a traumatic event, another might struggle with anxiety or depression due to genetic predispositions or life pressures. Recognizing this diversity is crucial. Just as each person has their own fingerprint, so too does their experience with mental and emotional health. Imagine a family gathering where everyone shares a different story about the same event. This is how varied the experiences of addiction and mental health can be. The key is to listen and understand, not to generalize or judge based on a single narrative. Personalized Paths to Healing Just as the experiences vary, so too must our approaches to support and healing. One size does not fit all in the realm of emotional and mental well-being. Some may find solace and recovery through therapy and medication, while others might turn to art, exercise, or spiritual practices. The art lies in finding what resonates with the individual, encouraging exploration, and supporting their choices with an open heart and mind. Consider the story of a young person who discovered a profound sense of peace and self-awareness through painting, something that traditional therapy sessions could not unlock for them. This is a testament to the power of personalized healing paths. The Foundations of Support Embracing a Culture of Openness Creating an environment where open discussions about addiction and mental health challenges are not just accepted but encouraged is pivotal. It’s about breaking down the walls of stigma and shame that too often silence those in need. By fostering a home where vulnerabilities can be shared without fear of judgment, we lay the groundwork for healing and connection. One family shared their tradition of “The Circle of Trust,” a monthly gathering where each member could share anything on their mind, knowing they would be met with understanding and support, not criticism. This practice became a cornerstone of their collective and individual healing journeys. The Power of Empathetic Listening Listening, truly listening, is a gift we can all give to those navigating the rough seas of addiction and mental health struggles. It’s not about offering solutions or advice but about being a compassionate witness to their experience. Through empathetic listening, we validate their feelings and struggles, making them feel seen and understood. A professional in the field often shares how simply sitting with someone in silence, offering a presence rather than words, can be a profound form of support. This act of silent solidarity can speak volumes, conveying empathy and understanding without a single word. Nurturing Connection and Belonging The feeling of being deeply connected to others, of belonging, is a fundamental human need. For those facing addiction and mental health challenges, this need is even more critical. Isolation can exacerbate feelings of despair and disconnection, while a sense of belonging can serve as a powerful antidote. Families and communities can play a crucial role in fostering this sense of connection. Organizing regular family activities, encouraging participation in community events, or simply ensuring that time is set aside for meaningful conversations can make a significant difference. Remember, it’s about quality, not quantity. A few moments of genuine connection can be more healing than hours of distracted or superficial interaction. Paths Forward Building Resilience through Understanding Educating ourselves about the complexities of addiction and mental health is essential. With understanding comes the ability to foster resilience, both in ourselves and our loved ones. It’s about moving beyond the surface level, seeking to comprehend the underlying causes and conditions that contribute to these challenges. This journey of learning should be approached with curiosity and an open mind. There are countless resources available, from books and documentaries to workshops and lectures, that can offer insights and expand our understanding. By deepening our knowledge, we equip ourselves with the tools to provide more effective support and advocacy. Advocating for Comprehensive Care Recognizing the need for a holistic approach to treatment and support, we must advocate for comprehensive care that addresses not just the symptoms but the root causes of addiction and mental health challenges. This includes access to mental health professionals, support groups, educational programs, and community resources. It’s also about recognizing the importance of integrating physical health, emotional well-being, and spiritual growth into the recovery process. Encouraging a loved one to engage in activities that nourish the body, mind, and soul can be an invaluable part of their healing journey. Celebrating Progress, No Matter How Small In the world of addiction and mental health recovery, progress can be slow and non-linear. It’s important to celebrate every step forward, no matter how small it may seem. Acknowledging achievements, whether it’s a day of sobriety, attending a therapy session, or simply engaging in self-care, can boost morale and reinforce the value of the journey. A professional in the field often shares stories of the “Jar of Progress,” where individuals write down their achievements, big or small, on pieces of paper and place them in a jar. Over time, this visual representation of progress becomes a powerful reminder of the journey and the steps taken towards healing. Conclusion Navigating the complexities of addiction and mental health challenges is a journey that requires compassion, understanding, and a willingness to embrace the nuances of human experience. By fostering environments of openness, understanding, and connection, we can support our loved ones in their paths towards healing and wholeness. Remember, the journey is as much about the steps taken as it is about the destination reached. Each moment of understanding, each act of compassion, each connection made, contributes to a foundation of support and love. It’s through these collective efforts that true healing can begin, not just for those we love but for ourselves as well. Why Should I Care? In the fabric of our lives, the well-being of our loved ones intertwines closely with our own. When a family member struggles with addiction or faces mental and emotional health challenges, it’s not just their journey — it becomes part of our journey too. Here’s why deeply engaging with and caring about this process is essential for everyone involved: For the Strength of Your Relationships The way we respond to a loved one’s struggles can significantly impact the quality and depth of our relationships. Showing empathy, offering support, and taking the time to understand their experiences can strengthen bonds, build trust, and foster a sense of security and belonging. It tells them, “You’re not alone in this.” This support can be the very lifeline they need during their darkest times. For the Health of Your Family and Community Addiction and mental health issues, when not addressed, can ripple through families and communities, affecting relationships, safety, and the well-being of all members. By caring and taking action, you contribute to a healthier, more resilient family and community. It’s about creating an environment where challenges are met with compassion and support, rather than stigma and isolation. For Your Own Growth and Well-being Engaging with these issues doesn’t just benefit the person struggling; it also offers an opportunity for personal growth. It challenges us to develop patience, understanding, and empathy. It can deepen our appreciation for the complexities of human nature and our own capacity for kindness and support. Moreover, learning how to navigate these challenges can improve our own mental and emotional resilience. For the Bigger Picture Caring about and understanding addiction and mental health challenges contribute to a broader societal change. It challenges stigmas and misconceptions, encouraging a more compassionate, informed, and supportive approach to these issues at a societal level. Your engagement can inspire others, contribute to breaking down barriers to care and support, and foster a more understanding and inclusive community. In essence, caring about and actively supporting loved ones facing these challenges is not just an act of love for them — it’s a commitment to the well-being of your family, community, and yourself. It’s a step towards building a world where challenges are met with understanding and compassion, where every individual feels valued and supported, and where healing and hope are accessible to everyone. Hey there, families! If you’re reading this, chances are you’re grappling with the complexities of a loved one’s journey through problematic substance use or perhaps addiction. It’s a path fraught with confusion, heartache, and often a sense of helplessness. But what if I told you that our collective battle against drugs is actually part of the problem, not the solution?

Understanding the Roots of Substance Use Before we dive deep, let’s pause and reflect on why people turn to alcohol and other drugs in the first place. At its core, substance use often stems from an attempt to soothe pain, whether it’s, social, emotional, physical, or psychological. It’s a form of self-medication, an attempt to silence the din of trauma, stress, or unmet needs. I get to ask myself, why would someone not want to be themselves for a few hours? Imagine a child, who instead of learning to navigate their emotions or heal from their wounds, they learn to find temporary solace in alcohol and other drugs. It’s not the substance that’s the core issue but the pain and the absence of healthier coping mechanisms. It’s the very real relationship between the person and the painkiller that gets to be explored. The Historical Context of Drug Prohibition Drug prohibition has a long and storied history, marked by the belief that criminalization is the key to eradicating drug use. Yet, this approach has not only failed to diminish use but has, paradoxically, led to the development of more potent and dangerous substances. It’s akin to trying to douse a fire with gasoline — the problem only intensifies. The Failure of a Punitive Approach

The Stigmatization of Addiction Stigma is a powerful force, silencing conversations and isolating those in the throes of addiction. It’s a barrier to healing, reinforcing shame and guilt in those who are already suffering. The roots of stigmatization are:

Alternative Approaches: A Light at the End of the Tunnel Amidst this landscape of challenge and despair, there’s a growing recognition that we need a new approach — one that embraces compassion, understanding, and evidence-based strategies. Success Stories from Around the World Globally, we’re seeing the positive impacts of harm reduction strategies and the decriminalization or legalization of drugs. These approaches prioritize health and safety over punishment, helping to break the cycle of addiction and its associated harms. Portugal is an example of brave and courageous leadership, when it comes to addressing the causes and conditions that lead to problematic use. The Benefits of a Health-Centered Approach Focusing on harm reduction and treatment rather than punishment can lead to decreased drug misuse, improved public health outcomes, and a significant reduction in the economic burden of substance use on society. A New Perspective on Healing The journey to supporting a loved one through substance use is complex, requiring patience, understanding, and an open heart. It’s about moving beyond the myopic view of drugs or the people who use them as the enemy, to understanding the underlying pain and trauma that fuels use. Compassionate Communication Opening a dialogue grounded in empathy and understanding is crucial. It’s about listening, truly listening, to the experiences and needs of your loved one without judgment or condemnation. Building a Supportive Environment Creating a SAFE, nurturing environment where your loved one feels seen, heard, and valued can make a world of difference. It’s about affirming their worth and supporting their journey towards healing and recovery.

Addressing substance use means looking beyond the physical aspect to the emotional and psychological facets of the experience of addiction. It involves a holistic approach that encompasses mental health support, trauma-informed care, and strategies to develop healthier coping mechanisms. Conclusion: A Call to Action for Families As we navigate this path together, let’s challenge the narratives that have long dominated our approach to drugs and addiction. By fostering understanding, compassion, and a commitment to evidence-based care, we can support our loved ones in finding their way back to health and wholeness. Remember, you’re not alone in this journey. It’s a collective struggle that calls for a collective response — one rooted in love, empathy, and an unwavering belief in the possibility of recovery. Together, we can pave a new path forward, transforming our approach to substance use from one of conflict to one of healing and hope. In this transformative journey, let’s hold onto the belief that change is possible, and that with the right support, understanding, and resources, our loved ones can find their way to a brighter, healthier future. |

AuthorTimothy Harrington's purpose is to assist the family members of a loved one struggling with problematic drug use and/or behavioral health challenges in realizing their innate strength and purpose. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

HoursM-F: 7am - 9pm

|

Telephone323-804-5555

|

|

Medical Disclaimer: The information available from this website has been prepared and/or obtained for general information, education, reference, and/or entertainment purposes only and is not intended to provide medical advice. The owner of this website is not a licensed doctor and is not providing medical advice, or diagnosing or treating any condition you may have. We are not your doctor.

You agree that you will not act upon anything contained in this website without first seeking professional medical advice.

You agree that you will not act upon anything contained in this website without first seeking professional medical advice.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed