What is Addiction?

|

Addiction, properly understood, is neither a disease to be cured—though it has aspects of a disease—nor a problem to be eliminated. On the contrary, addiction is the individual’s attempt to solve a quandary. Before we can address addiction, this simple fact must be understood.

What is the problem that addiction is meant to resolve? As the Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards wrote about his own heroin habit, it can be a search for oblivion. He writes of “the contortions we go through just not to be ourselves for a few hours.” Why would a person long to escape themselves? Because, as a result of their life experiences, they are intensely distressed and may feel trapped within their situation. To put it another way, all the addictive substances (and addictive behaviors) soothe pain or at least distract from pain. Specifically, abusive substances like opiates are powerful painkillers, both physical and emotional; as is cocaine; as is alcohol. Hence, the question is not why the addiction, but why the pain? And, again, the answer resides neither in genes nor in “choices,” but in the lives and experiences of the addicts. Gabor Mate |

|

A Biopsychosocial Approach to Understand Addiction

Humans are social creatures. A biopsychosocial model incorporates the scientific understanding that the biology of human beings, including their brain biology, is from conception until death is in profound interaction with and is shaped by their relationships with other people and by their own emotional states. In real life the physiology of people cannot be separated from their minds.

As the psychiatrist Thomas Hora said, “When we get the what, we know the how.” Before we ask what to do about addiction, we have to define our perspective. What we do about any phenomenon depends on our understanding of it.

The available information about addiction is inadequate, hence the high failure rate of programs. The mainstream view of addiction (as compared with the medical view) is that addiction is a matter of individual choice, moral failure, or weakness. Thus exist the approaches aimed at deterrence or punishment.

The medical view is that addiction is a disease of the brain, with disordered brain circuits and disordered behaviors. This view is both accurate, so far as it goes, and hopelessly narrow. It is accurate because the addicted brain is demonstrably a physiologically dysfunctional brain, but narrow because it seeks to explain the dysfunction in strictly physiological and biochemical terms, without recognizing the emotional and social inputs into how the brain operates. (See biopsychosocial above.) Different as they are, these two views share a lack of understanding that addiction is a product of and a response to life experience; in fact, it’s neither a conscious choice nor an inherited illness.

Addiction is a complex issue and to make progress, it should be addressed from several angles.

Gabor Mate

Books

|

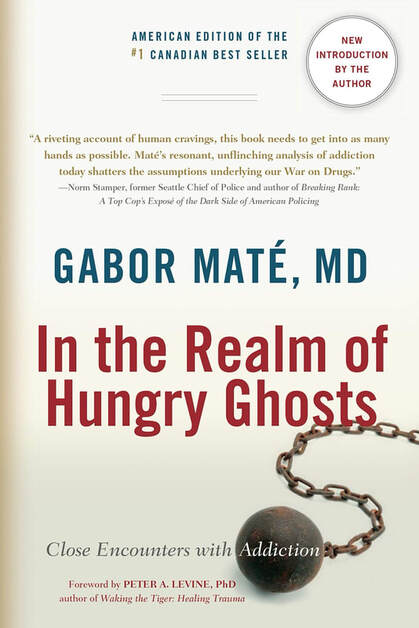

Hungry Ghosts (U.S. Title: In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction)From street-dwelling drug addicts to high-functioning workaholics, the continuum of addiction cuts a wide and painful swath through our culture.

Blending first-person accounts, riveting case studies, cutting-edge research and passionate argument, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction (available for order in Canadian, U.S. and UK Editions) takes a panoramic yet highly intimate look at this widespread and perplexing human ailment. Countering prevailing notions of addiction as either a genetic disease or an individual moral failure, Dr. Gabor Maté presents an eloquent case that addiction – all addiction – is in fact a case of human development gone askew. Dr. Maté, who for twelve years practiced medicine in Vancouver’s notorious Downtown Eastside – North America’s most concentrated area of drug use, begins by telling the stories of his patients, who, in their destitution and uniformly tragic histories, represent one extreme of the addictive spectrum. With his trademark compassion and unflinching narrative eye, he brings to life their ill-fated and mostly misunderstood struggle for relief or escape, through substance use, from the pain that has tormented them since childhood. He also shows how the behavioural addictions of society’s more fortunate members – including himself – differ only in degree of severity from the drug habits of his Downtown Eastside patients, and how in reality there is only one addiction process, its core objective being the self-soothing of deep-seated fears and discomforts. |